The Fukushima disaster continues, and will do so for a long time to come. This is hardly surprising given the overwhelming force the plant was exposed to, which far exceeded the worst case scenario it was designed to withstand.

The 2 pictures above were taken at Fukushima Dai-Ni

The immediate devastation from the earthquake and tsunami was immense, even before the accident began.

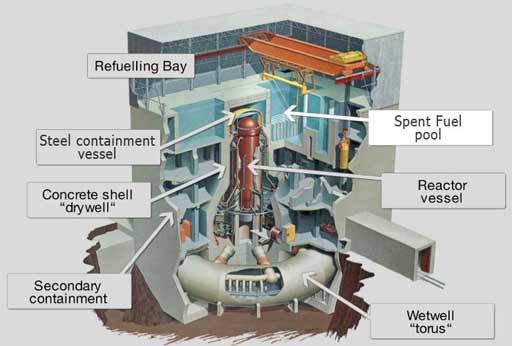

As we have seen over the past several weeks, the loss of power to the site, and subsequent inability to circulate coolant in the reactors and the spent fuel pools, led to explosive consequences. We saw a series of hydrogen explosions at units 1, 3 and 2 and 4, and have seen at least three partial meltdowns, with varying degrees of apparent containment breach. Hydrogen is produced as an exothermic reaction when the fuel cladding reacts with water steam at high temperatures (Zr + 2 H2O -> ZrO2 + 2 H2), indicating damage to the reactor core from loss of coolant.

The first image below shows the four units, with unit 4 on the far left and unit 1 on the far right. The second shows a close up of units 3 and 4, where the buildings sustained the greatest visible damage.

Unit 4 is particularly interesting, since the reactor had been offline for maintenance at the time of the earthquake, with its fuel removed and stored in the spent fuel pool. The explosion in this unit must have been related to this accumulation of fuel. The pool is believed to have been damaged, leading to loss of cooling water and partial exposure of the fuel rods.

The first image below is of unit 4 and the second is a close up inside the unit taken by helicopter:

It is not difficult to see how the spent fuel pool, which is situated above the reactor, could have come to be damaged.

Operators have been spraying the ground surrounding the plant with resin in order to prevent radioactive dust from the debris from becoming airborne:

Engineers have been working intensively to restore power to the site under very difficult conditions:

In the meantime, essential cooling has been ad hoc through the use of seawater, but this results in a salt build up that leads to further difficulty cooling the plant and also to rapid corrosion at high temperatures. Salt accumulation will need to be flushed out with fresh water. Seawater spraying into cracked vessels has also led to the accumulation of large quantities of radioactive water. As a result, 10,000 tons of contaminated water (measuring about 500 times above the legal limit for radioactivity) were emptied into the sea in order to make room for much more highly contaminated water.

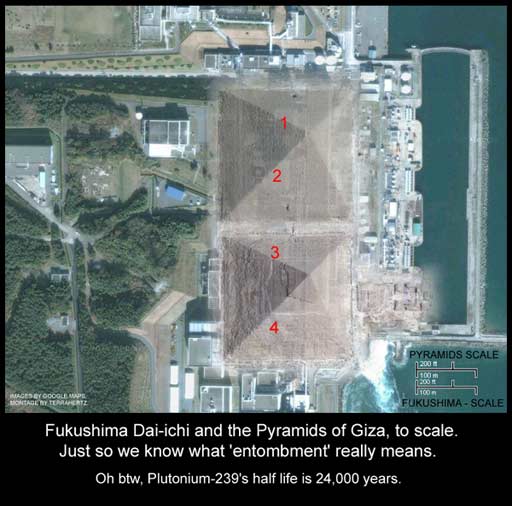

In addition, the world’s largest concrete pumps are being sent to Japan, first to pump water, and later perhaps to create a concrete sarcophagus. Here’s one that arrived on an Antonov plane.

Pumps used at the site would have to be abandoned there as they will be too radioactive to recover. The dimensions of a sarcophagus entombing at least 4 reactors would have to be truly gargantuan – considerably larger than the pyramids at Giza per reactor. This would be no small undertaking. Alternatively, Japan may attempt to drape the plants with fabric. There are clearly no easy long term solutions.

The accident process is being reconstructed, often from foreign sources through nuclear forensics. French nuclear company Areva initially (and inadvertently) provided a particularly detailed explanation of the accident sequence in the early days, indicating a more serious accident in unit 2 than in units 1 and 3. At unit 2, the condensation chamber at the base of the reactor appears to have been damaged, leading to the loss of highly radioactive water into the environment. Thus, while unit 2 appears to the least damaged from the outside, the internal damage poses a larger threat than units 1 and 3.

This analysis fits with subsequent events. Operators faced a leak of highly radioactive water from a maintenance pool associated with unit 2. This took desperate measures to plug. Concrete initially failed to harden, whereupon operators resorted to sawdust, shredded newspapers, special polymers and screens were used. According to TEPCO, the leak was plugged on April 6th.

The leak caused radiation levels to spike in the sea surrounding the plant:

The operator of Japan’s stricken Fukushima nuclear plant said Tuesday that it had found radioactive iodine at 7.5 million times the legal limit in a seawater sample taken near the facility, and government officials imposed a new health limit for radioactivity in fish. The reading of iodine-131 was recorded Saturday, Tokyo Electric Power Co. said. Another sample taken Monday found the level to be 5 million times the legal limit. The Monday samples also were found to contain radioactive caesium at 1.1 million times the legal limit.

It has also caused diplomatic difficulties with neighbours:

Regarding the release of radiation contaminated water into the ocean from Fukushima I Nuclear Power Plant, the South Korean government conveyed its worries to Japan’s Foreign Ministry through its Embassy in Japan at night of April 4 [when TEPCO started dumping], that “this may cause problems in international law.”

India has already banned the import of produce from Japan, and other countries are likely to follow suit. Seafood is likely to be the most affected. The Japanese authorities are still saying this is safe, although they have imposed new standards:

The plant operator insisted that the radiation will rapidly disperse and that it poses no immediate danger, but an expert said exposure to the highly concentrated levels near the Fukushima Dai-ichi plant could cause immediate injury and that the leaks could result in residual contamination of the sea in the area.

The new levels coupled with reports that radiation was building up in fish led the government to create an acceptable radiation standard for fish for the first time, and officials said it could change depending on circumstances. Some fish caught on Friday off Japan’s coastal waters would have exceeded the new limit.

Nuclear analyst Arnie Gundersen more recently identifies unit 2 as the reactor of most concern. There is a combination of temperature above boiling point and no additional pressure inside the reactor. The implication is that unit 2 is not currently water cooled and likely contains hot air or hydrogen instead. There is also not pressure in the containment system at unit 2. A containment breach in the bottom of unit 2 would be consistent with these observations.

Unit 1 has both high temperature and elevated pressure inside the reactor, indicating perhaps a water/steam combination, Unit 3 has low pressure and a temperature at boiling point, indicating relative stability. Both these units have somewhat elevated pressure inside the containment structures. Operators at Fukushima have sent robots into the damaged units to assess the radiation currently present:

The data released by TEPCO for units 1 and 3 are translated as follows:

Reactor 1 building: Date and time: 4:40PM to 5:30PM, April 17, 2011 Radiation (1st floor, through the north door): 10 to 49 milli-sievert/hr Reactor 3 building: Date and time: 11:30AM to 1:30PM, April 17, 2011 Radiation: 28 to 57 milli-sievert/hr

According to TEPCO, there were a lot of debris inside the Reactor 3 building, and the robots had a hard time moving forward and didn’t go much beyond the door.

Part of the reason why they had the robots enter through the north door was because of the high radiation level at the south door.

April 16, the radiation level at the south door to the Reactor 1 building was measured at 270 milli-sievert/hr. The distance between the north door and the south door is about 30 meters, according to TEPCO. The radiation right outside the north door was also measured on April 16, and it was 20 milli-sievert/hr.

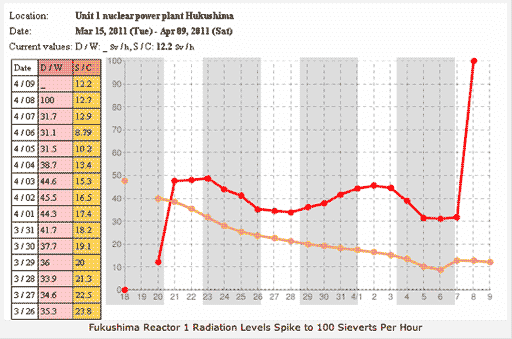

Apparently the unit 2 building was too steamy for the robots to record readings. This is also the location where readings are most urgently needed. Official Japanese radiation data have shown some disturbing values over the last couple of weeks. See for instance this screen shot for unit 1 taken April 9th:

On April 17th the same site had the following radiation levels recorded for units 1-3:

Reactor 1 Dry Well: 121.4 Sv/hr Suppression chamber: 97.5 Sv/hr Reactor 2 Dry Well: N/A Suppression Chamber: 131 Sv/hr Reactor 3 Dry Well: 253.2 Sv/hr Suppression Chamber: 103.9 Sv/hr

A single dose of about 5Sv would be fatal in about 50% of cases according to the IAEA. The allowable emergency dose for nuclear workers has been climbing recently. It was originally 100 mSv/yr, was raised to 250 mSv/yr and is now to be raised again, likely to 500mSv/yr. Translated from Nihon Television News 24 on April 18th:

The radiation exposure limit for workers at nuclear power plants is 100 milli-sievert/year, but the limit has been raised to 250 milli-sievert/year to deal with the Fukushima I Nuke Plant accident. According to the government sources, the higher limit is being considered because it is getting increasingly difficult to have enough workers to work on the plant. Also, the radiation inside the Reactor buildings is high, and the annual limit of 250 milli-sieverts may not be high enough to achieve the goals laid out by the TEPCO road map.

The international standard allows 500 milli-sievert/year in an emergency work, but it hasn’t been decided how high the new limit will be. The government will carefully assess the timing of announcement, keeping in consideration the health concerns of the workers and the public opinion.

It continues to be difficult to secure skilled and experienced workers at Fukushima, likely because they know what happened to their counterparts at Chernobyl.

In my view the Japanese government is being far too sanguine about the risks in the neighbourhood of the stricken plant, while risks far from the plant are often overstated. The evacuation zone may be extended in light of continuing aftershocks, but probably not by enough, for logistical reasons:

One reason for the reluctance of the Japanese government to widen the evacuation from 20km to 40 km is because it will need to relocate another 130,000 people from the affected zone on top of the 70,000 people who are already evacuated from the 20km zone. So where are they going to resettle this 200,000 people as they can never return to their homes for the next few hundred years.

If the evacuation zone be enlarged to 80 km as recommended by the IAEA, it is estimated that they need to evacuate another 1.8 million people or making the total of 2 million residents out from the danger zone. Where are they going to put those 2 million refugees?

Another reason for the reluctance to widen the evacuation zone is due to logistics. The Tohoku expressway is a national expressway in Japan and links Tohoku region in the northernmost region in the Honshu Island with the Kanto region and Greater Tokyo.

So if the government decided to entomb the Fukushima reactors, it will need to cordoned off an area with a radius of 50km from Fukushima. Hence the cost of not able to move people and goods from Tokyo to Northern Honshu will be staggering . Moreover it will also prohibit traveling using train services as the main train track passes through the region in Sendai-Fukushima-Iwate and runs parallel to the coast.

The risk of further adverse events at the unstable plant will remain high for months, if not years, to come, and reactors at Onagawa and Fukushima II may also be vulnerable. Many other locations should urgently review their safety standards and design-basis accident scenarios in light of the catastrophe that is unfolding in Japan.