Last week, in Get Ready for the North American Gas Shock, The Automatic Earth evaluated the prospects of shale gas, a supposedly plentiful and clean fuel upon which many have placed their hopes of both energy supply and handsome profits. The first part of our shale gas analysis concentrated on supply and EROEI (energy returned on energy invested), pointing out that reserves are very much overstated and that the sector is in fact in a major bubble. In this follow up, we are going to assess the other major claim – that shale gas is a clean energy source, and would constitute an improvement in environmental terms over reliance on oil and coal.

Fracking: The Great Shale Gas Rush

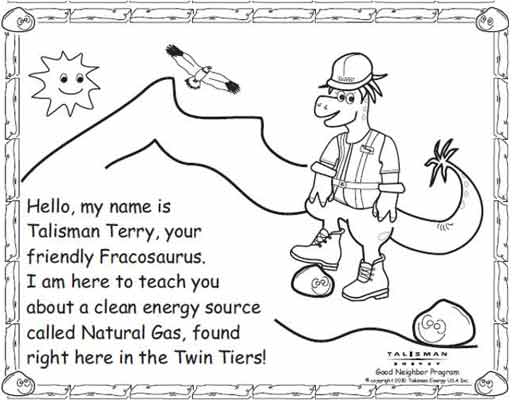

Along with wind, solar, and nuclear power, natural gas is crucial to Obama’s goal of producing 80 percent of electricity from clean energy sources by 2035. But the drilling is taking place with minimal oversight from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. State and regional authorities are trying to write their own rules—and having trouble keeping up.

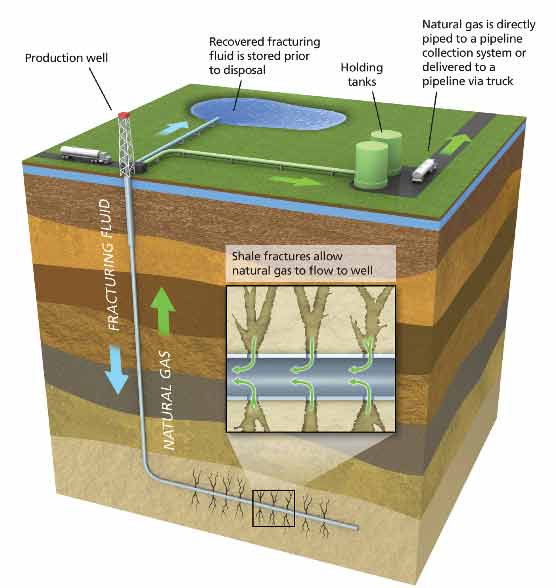

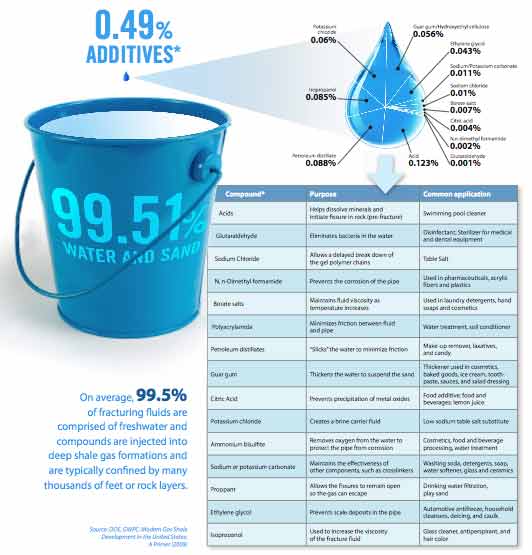

Shale gas is contained in impermeable reservoir formations deep beneath the surface. In order to release the gas for extraction, the rock must be hydraulically fractured (fracked). Pipes are inserted by drilling first vertically into the formation, then horizontally along it in many different directions from a common well pad. The pipes are constructed like a soaker hose, with holes along their length. A mixture of water (99%), sand and a proprietary mixture of chemicals is injected thousands of feet down under very high pressure, multiple times per well.

The water – 2 to 6 million gallons per well – (a challenge in arid regions) fractures the formation rock where it exits through the holes in the pipe. The sand acts as a propping agent, entering the fractures and keeping conduits open while providing for permeability to gas flow. The released gas then flows into and up the pipe to be collected at the surface. The long horizontal pipes allow for a large surface area in contact with gas-bearing rock, maximizing extraction.

Fracking was first implemented by Halliburton in 1949, but only became common much more recently in combination with horizontal drilling, and once the companies had been exempted from important environmental legislation.

It really wasn’t until 2004 that fracking really took off, the year that the EPA declared that fracking “posed little or no threat” to drinking water. Weston Wilson, a scientist and 30-year veteran of the agency, who sought whistleblower protection, emphatically disagreed, saying that the agency’s official conclusions were “unsupportable” and that five of seven members of the review panel that made the decision had conflicts of interest. (Wilson has continued to work at the EPA, and continues to be publicly critical of fracking.)

A year later, Congress passed the Energy Policy Act with a “Halliburton loophole,” a clause inserted at the request of Dick Cheney, who had been Halliburton’s CEO before becoming vice president. The loophole specifically exempts fracking from the Safe Drinking Water Act, the Clean Water Act, the CLEAR Act, and from regulation by the Environmental Protection Agency, and it unleashed the largest and most extensive drilling program in history, according to Josh Fox, the creator of the film Gasland.

The chemicals added serve a number of purposes, including preventing the growth of slime organisms, keeping the sand in suspension, preventing scale build-up and reducing friction. Fracking fluids typically contain biocides, surfactants, and corrosion and scale inhibitors, among other ingredients. The exact composition of the fluid is not made public, although it may be revealed to local regulators. Many of the chemicals used are toxic or carcinogenic, and their use is highly contentious.

Although added chemicals comprise less than 1% of the fracking fluid, that still amounts to a small percentage of a very large number. Given the enormous quantities of fluid involved. and the toxicity of the additives, concern is justified.

By examining drillers’ patent applications and government worker health and safety records, some environmentalists and regulators in the US have been able to piece together a list of some of the fracking fluid ingredients. These include potentially toxic substances such as diesel fuel (which contains benzene, ethylbenzene, toluene, xylene, and napththalene), 2-butoxyethanol, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, methanol, formaldehyde, ethylene, glycol, glycol ethers, hydrocholoric acid, and sodium hydroxide.

Half or more of the fracking fluid, along with water from the rock formation (which can contain heavy metals and other minerals), typically returns to the surface for disposal, where it is stored in ponds. These ponds can unfortunately leak, and evaporation of volatile chemicals can cause local air pollution. Disposal is expensive, both in financial and energy terms. The need for energy-intensive disposal lowers the Energy Returned on Energy Invested (EROEI) for the shale gas extraction life cycle.

A number of states allow fracking fluid to be disposed of to land, but this can have significant consequences.

A study that argues for more research into the safe disposal of chemical-laced wastewater resulting from natural gas drilling found that a patch of national forest in West Virginia suffered quick and serious loss of vegetation after it was sprayed with hydraulic fracturing fluids. The study, by researchers from the United States Forest Service, was published this month in the Journal of Environmental Quality. It said that two years after liquids were legally spread on a section of the Fernow Experimental Forest, within the Monongahela National Forest, more than half of the trees in the affected area were dead. [..] Almost immediately after disposal, the researchers said, nearly all ground plants died. After a few days, tree leaves turned brown, wilted and dropped; 56 percent of about 150 trees eventually died.

The gas industry claims that there are no health or environmental effects from the fracking process, but these claims are hotly disputed. A primary concern is the potential for aquifer contamination, which can have significant adverse impacts on people’s well water. In rural areas, there may be a very large number of drinking water wells. While the fracked formations are generally many thousands of feet below aquifers, poorly constructed well casings can leak. Also, natural faults within the rock strata could allow fracking fluids or methane or both to migrate upwards.

Shale gas wells can be very densely packed, and in many places well drilling and fracking activity have increased by an order of magnitude or more in a few short years thanks to the frenetic activity brought about by the shale gas bubble.

Jessica Ernst says she’s “still getting used to” being compared to Erin Brockovich (the environmental activist made famous by Julia Roberts’ film portrayal ten years ago). The comparison comes easy because the outspoken Ernst, a landowner in the town of Rosebud, Alberta, is one of the few Albertans who have publicly criticized hydraulic fracturing [..]

After her well water was contaminated by nearby fracking in 2006, Ernst decided to go public, showing visiting reporters how she could light her tap water on fire, and speaking out about Alberta land owners’ problems with the industry, especially Calgary-based EnCana. EnCana is Canada’s second biggest energy company (after Suncor) and is now also a major player in British Columbia, with hundreds of natural-gas wells in the province.

Ernst, a biologist and environmental consultant to the oil and gas industry, says EnCana “told us ‘we would never fracture near your water.’ But the company fracked into our aquifer in that same year [2004].” By 2005, she says, “My water began dramatically changing, going bad. I was getting horrible burns and rashes from taking a shower, and then my dogs refused to drink the water. That’s when I began to pay attention.” More than fifteen water-wells had gone bad in the little community. Tests revealed high levels of ethane, methane, and benzene in Ernst’s water.

Dimock, Pennsylvania, is another region where significant impacts have undoubtedly manifested. Consider the experience of the Sautner family and their neighbours:

Drilling operations near their property commenced in August 2008…..Within a month, their water had turned brown. It was so corrosive that it scarred dishes in their dishwasher and stained their laundry. They complained to Cabot[Houston-based Cabot Oil & Gas, a midsize player in the energy-exploration industry], which eventually installed a water-filtration system in the basement of their home. It seemed to solve the problem, but when the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection came to do further tests, it found that the Sautners’ water still contained high levels of methane. More ad hoc pumps and filtration systems were installed. While the Sautners did not drink the water at this point, they continued to use it for other purposes for a full year.

“It was so bad sometimes that my daughter would be in the shower in the morning, and she’d have to get out of the shower and lay on the floor” because of the dizzying effect the chemicals in the water had on her, recalls Craig Sautner, who has worked as a cable splicer for Frontier Communications his whole life. She didn’t speak up about it for a while, because she wondered whether she was imagining the problem. But she wasn’t the only one in the family suffering. “My son had sores up and down his legs from the water,” Craig says. Craig and Julie also experienced frequent headaches and dizziness.

By October 2009, the Department of Environmental Protection had taken all the water wells in the Sautners’ neighborhood offline. It acknowledged that a major contamination of the aquifer had occurred. In addition to methane, dangerously high levels of iron and aluminum were found in the Sautners’ water. The Sautners now rely on water delivered to them every week by Cabot. The value of their land has been decimated….They desperately want to move but cannot afford to buy a new house on top of their current mortgage.

Frenetic activity is not the best circumstance for ensuring care and attention to detail, even when the price of carelessness can be effectively permanent groundwater contamination with highly toxic or explosive substances. Accidents can happen. For instance a well in Clearfield County, Pennsylvania, experienced a blow-out on June 3rd 2010 that was determined to have been easily preventable. Had the released gas ignited, the consequences could have been dire. As it was, gas, along with 35,000 gallons of drilling fluid, spewed from the well for 16 hours before the situation was brought under control.

DEP Secretary John Hanger announced that an independent investigation confirmed that the incident was preventable and EOG Resources ignored industry standards by failing to install proper barriers in the well and hiring uncertified operators. Hanger also said that EOG Resources failed to alert emergency authorities until several hours after the blowout, which hindered the state’s response.

“Make no mistake, this could have been a catastrophic incident,” Hanger said. “Had the gas blowing out of this well ignited, the human cost would have been tragic, and had an explosion allowed this well to discharge wastewater for days or weeks, the environmental damage would have been significant.” John Vittitow, an experienced petroleum engineer hired by the DEP to conduct the investigation, made an eerie comparison to the Deepwater Horizon disaster in the gulf as he described the failed blowout preventer that led to the incident. Vittitow said that EOG Resources only installed one pressure barrier during a well clean-out procedure, while industry standards call for at least two barriers in case of failure.

Hanger admitted that state regulations on well operations are broad and regulators would have to be “more prescriptive” to ensure that well operators use at least two barriers in the future. Vittitow’s investigation also revealed that the C. C. Forbes operators lacked industry certifications that are mandatory in most companies.

It is no surprise that regulators are struggling to keep pace with events and little authoritative research has been done on environmental effects. Received wisdom has become that shale gas is both clean and plentiful, and it can be very difficult to get funding to challenge received wisdom and powerful vested interests in any field. A team from Duke University recently undertook research on well water impact in New York and Pennsylvania, sampling 68 private wells at varying distances from from drilling activity.

The trends were immediately clear: those within 1km of an active drilling site were much more likely to have high levels of methane, on average 17 times higher than those sites more distant from active drilling. That average covers a broad range, too. Some sites were indistinguishable from the typical inactive well, while others had concentrations of methane between 19.2 and 64 mg/l, enough to pose an explosive hazard, and high enough to qualify for hazard mitigation under the Department of the Interior’s rules.

The Duke team has been criticized by the shale gas industry for lacking baseline data, yet the industrial players themselves have the necessary data and refuse to release it.

Ever since high-profile water contamination cases were linked to drilling in Dimock, Pa., in late 2008, drilling companies themselves have been diligently collecting water samples from private wells before they drill, according to several industry consultants who have been working with the data. While Pennsylvania regulations now suggest pre-testing water wells within 1,000 feet of a planned gas well, companies including Chesapeake Energy, Shell and Atlas have been compiling samples from a much larger radius—up to 4,000 feet from every well. The result is one of the largest collections of pre-drilling water samples in the country.

“The industry is sitting on hundreds of thousands of pre and post drilling data sets,” said Robert Jackson, one of the Duke scientists who authored the study, published May 9 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences….”I asked them for the data and they wouldn’t share it.”

Air pollution can also be a major issue in fracking centres, some of which are densely populated.

The picture from Dish is not pretty. A set of seven samples collected throughout the town analyzed for a variety of air pollutants last August found that benzene was present at levels as much as 55 times higher than allowed by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ). Similarly, xylene and carbon disulfide (neurotoxicants), along with naphthalene (a blood poison) and pyridines (potential carcinogens) all exceeded legal limits, as much as 384 times levels deemed safe. “They’re trying to get the pipelines in the ground so fast that they’re not doing them properly,” says Calvin Tillman, Dish’s mayor. “Then you’ve got nobody looking, so nobody knows if it’s going in the ground properly…. You just have an opportunity for disaster here.”

Dish sits at the heart of a pipeline network now tuned to exploit a gas drilling boom in the Fort Worth region. The Barnett Shale, a geologic formation more than two kilometers deep and more than 13,000 square kilometers in extent, holds as much as 735 billion cubic meters of natural gas—and the city of Fort Worth alone boasts hundreds of wells, according to Ed Ireland, executive director of the Barnett Shale Energy Education Council, an industry group. “It’s urban drilling, so you literally have drilling rigs that are located next door to subdivisions or shopping malls.”

Air pollution from fracking in agricultural areas can also have significant negative impacts.

According to Jaffe, ozone is more lethal to crops than all other airborne pollutants combined, and of all crops, few are more susceptible to it than clover, a nutrient-rich feed that is critical to his method of sustainable cattle raising. While ozone is normally associated with automobile exhaust, fracking generates so much of it that Sublette Country, Wyo., has ozone levels as high as Los Angeles. This, despite the fact that it has fewer than 9,000 residents spread out over an area the size of Connecticut. What it does have is gas wells.

Besides the effect of ground-level ozone on animal feed, there can be other more direct impacts on livestock and on farmers’ ability to make a living.

Last year, the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture quarantined 28 cattle belonging to Don and Carol Johnson….The animals had come into wastewater that leaked from a nearby well that showed concentrations of chlorine, barium, magnesium, potassium, and radioactive strontium. In Louisiana, 16 cows that drank fluid from a fracked well began bellowing, foaming and bleeding at the mouth, then dropped dead.

Livestock farmers are concerned that the mere presence of wells in the area could lead to suppliers ceasing to purchase their animals, for fear of contamination, whether or not animals do in fact come into contact with noxious chemicals in the air or water. They are also concerned about the lack of regulation and oversight of the industry as it may impact of their livelihoods.

For the most part, state and federal governments have turned a blind eye to the problems brought about by fracking. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) claims that it has no jurisdiction to investigate matters related to food production, a contention disputed by Congressman Maurice Hinchey (D-NY), who wrote a report urging the EPA to study all issues associated with fracking. A concerned farmer who prefers not to be identified forwarded me an email written to him by Jim Riviere, the director of the Food Animal Residue Avoidance Databank, a group of animal science professors that tracks incidents of chemical contamination in livestock.

Riviere wrote that his group receives up to 10 requests per day from veterinarians dealing with exposures to contaminants, including the byproducts of fracking. Nonetheless, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) has slashed funding to his group. “We are told by the newly reorganized USDA that chemical contamination is not their priority,” Riviere wrote.

Land owners are concerned about the value of their property, since some banks will not grant mortgages on real estate in fracked areas. As is often the case perception, particularly fear of risk, matters a great deal. Of course on the other side of the financial equation, a lot of revenue is dependent on the shale gas business. There are both winners and losers. For instance, in some states huge amounts of state pension funds are invested in shale gas companies.

In Pennsylvania, where 2,516 wells have been drilled in the last three years, $389 million in tax revenue and 44,000 jobs came from gas drilling in 2009, according to a Penn State report.

A number of jurisdictions either have banned fracking or are considering doing so. Quebec decided in March 2011 to wait for a detailed environmental study of the process, despite the putative value of the gas contained in the Utica shale formation and the private capital committed to the industry. Acceptance of the practice there, where there is no history of oil and gas exploration, is the lowest in Canada at 22% (compared to 46% in Alberta where the oil and gas industry is well established).

It has been a swift fall from grace for junior exploration companies whose fortunes are tied to Quebec’s nascent shale gas industry. Calgary-based Questerre Energy Corp., worth $800-million only a year ago, has a market capitalization barely one fourth of that today as investors cashed out following the Quebec government’s decision in March to put commercial hydraulic fracturing drilling on hold pending a detailed environmental review. Junex Inc. and Gastem Inc. aren’t faring any better. Each has seen its stock fall more than 50% off their 52-week highs on the Toronto Venture Exchange [..]

For Questerre, Quebec’s decision forced a brutal reckoning. The company holds development rights to more than one million gross acres of farmland along the southern flank of the St. Lawrence River in Quebec, smack in the middle of what has become known as the Utica shale gas formation. It estimates its property could yield a prospective recoverable resource of 18 trillion cubic feet. Its entire business plan was focused on developing Quebec gas [..]

Quebec has now decided it will not approve shale gas development until it’s proven safe by independent study. A panel of 11 experts has been mandated to undertake a strategic environmental assessment expected to take between two and three years. In the meantime, the province has cancelled exploration permits without compensation and issued a new set of regulations to govern shale gas development. Detailed administrative practices should follow.

Others jurisdictions are contemplating lifting bans already imposed, as the supposed benefits may seem simply too enticing. New York state, underlain by the Marcellus Shale, is suggesting a compromise, by allowing fracking in some locations, while attempting to protect watersheds and other sensitive locations. The decision is not popular.

Gov. David A. Paterson vetoed a bill passed by the Legislature last year that would have formally banned hydrofracking, but effectively put a ban into place until further study was completed. The Cuomo administration is seeking to lift what has effectively been a moratorium in New York State on hydraulic fracturing [..]

The process would be allowed on private lands, opening New York to one of the fastest-growing — critics would say reckless — areas of the energy industry. It would be banned inside New York City’s sprawling upstate watershed, as well as inside a watershed used by Syracuse, and in underground water sources used by other cities and towns. It would also be banned on state lands, like parks and wildlife preserves. It will most likely take months before the policy becomes official [..]

“This report strikes the right balance between protecting our environment, watersheds and drinking water, and promoting economic development,” said Joseph Martens, the commissioner of the department, a state agency controlled by the governor’s office.

It is not difficult to imagine the cause for opposition, since the Marcellus Shale lies beneath the largest unfiltered drinking water supply system in the USA, which provides over a billion gallons of water per day to New York City. Industry insider James Northrup, recently relocated from Texas to New York State, explains a number of the difficulties associated with the Macellus Shale in particular.

In summary, Mr Northrup points out that the rock formation of the Marcellus is particularly tight. The pressure required to frack the formation horizontally can be up to 15,000 psi (equivalent to the pressure 6 miles beneath the ocean being applied to several million gallons of water), which is much higher than was necessary for the older vertical wells in the Barnett Shale where the existing regulations were developed. This is like exploding a substantial pipe bomb underground in a geologically complex area where there is poor seismic data.

In other words, no one knows where the many faults are, and no one can dismiss the risk that racking fluid will end up in an aquifer. Oil based fluids, being lighter than water, will rise to the top of contaminated aquifers, ending up disproportionately in well water. Mr Northrup explains that the industry need not use toxic chemicals, and indeed should not, especially where the risk of groundwater contamination appears to be uncomfortably high. Even without toxic chemicals, Mr Northrup argues that fracking should not happen where seismic data is inadequate, as gas migration can still represent an explosion hazard.

Geologist Arthur Berman also has major concerns regarding the Marcellus Shale. He feels that the risk of capital destruction is unusually high, thanks to the large extent of the play which will make it more difficult to identify the core areas, or sweet spots, that shale gas plays always contract to. Existing gas pipeline infrastructure is inadequate and will require time to build out, but gas wells are being drilled now.

Valuable natural gas liquids, which must be removed prior injecting the gas into a pipeline, will be difficult to separate given the insufficient fractionation plant capacity. Obtaining permission for the very high volume water withdrawals required is likely to be problematic, as is transporting waste water to the few waste treatment plants in the region.

In addition, high population density in the area of the play will make it far more difficult to assemble acreage blocks, and will heighten the potential impact of any accidents. The objections may be legion, as the large population at risk expresses its intolerance of that risk.

Given the poor economics and low EROEI of shale gas in general. It is very difficult to argue that fracking, particularly in areas like the Marcellus Shale, makes sense. Unconventional gas is far from being a clean fuel when the whole lifecycle is considered. In fact considering the substantial potential for releases of fugitive methane emissions, one cannot even argue that unconventional gas is an improvement in comparison with burning coal when it comes to climate impact, let alone an improvement on other environmental fronts.

Shale gas is simply another Faustian bargain that humanity should not be making. We run substantial long term risks, which we socialize, for the sake of short term private profits.

This is the typical human modus operandi, but it is high time we learned from our mistakes.